UK Solar Inefficiency:

A Critical Obstacle

Solar power a have a role in the UK’s energy mix, but where it is built matters. Placing large solar farms next to communities and on productive farmland carries long-term costs to security, soil, democracy, landscape, and food resilience—costs that are avoidable through better planning and smarter siting.

Britain's Solar Underperformance:

A Global Bottom Tier

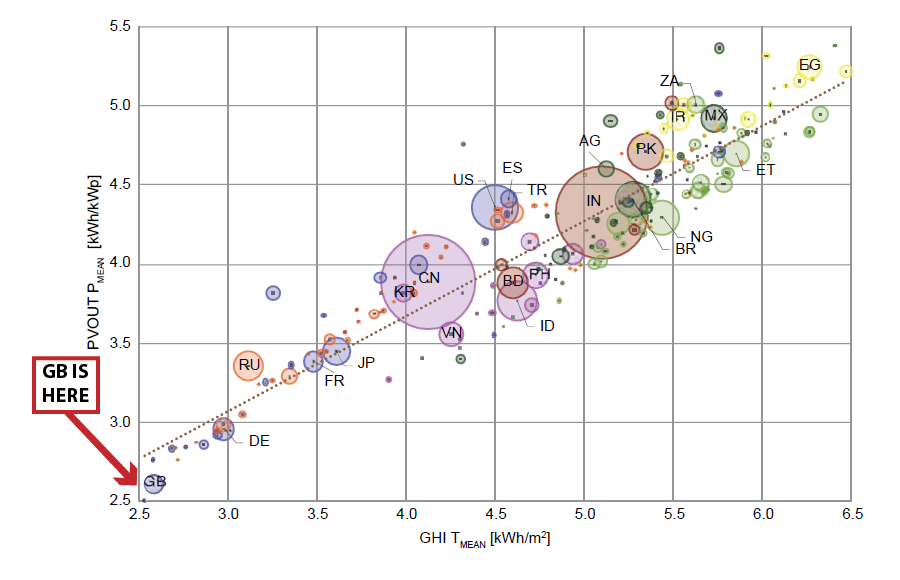

Authoritative World Bank data places the UK in the lowest global tier for solar PV output, consistently below 3.5 kWh/kWp/day. Independent analyses paint an even bleaker picture, citing an alarming average of just 2.61 kWh/kWp/day—the lowest recorded anywhere. This isn’t just an inefficiency; it’s a fundamental challenge to our energy ambitions.

Even with an ambitious target of 47 GW solar capacity by 2030, this technology is projected to fulfill less than 13% of the UK’s electricity demands. This limited contribution is further hampered by inherent high intermittency and critically low resilience, raising serious questions about energy security and stability.

A Global Low: UK Solar PV Efficiency

Among lowest globally for PV production

Limited Impact: Projected Contribution

Maximum projected electricity from 47 GW capacity

Average Practical PV Power Potential at Level 1 (PVOUT) Compared to Theoretical Potential (GHI) from The World Bank

In East Durham, large solar farm proposals are being driven by grid convenience rather than land suitability, placing pressure on productive farmland and rural landscapes, overlooking cumulative impacts and local consent, increasing security and resilience risks, and exposing the absence of a clear planning hierarchy that prioritises rooftops and brownfield land as required by the County Durham Local Plan.

Security, safety, and resilience concerns in open countryside

Large solar farms in East Durham are typically unstaffed and remote, increasing vulnerability to theft, vandalism, and disruption. These risks engage:

CDLP Policy 31 (Amenity and Pollution), where crime, lighting, fencing, and surveillance can affect residential amenity, and

Policy 34 (Pollution Control), where damaged infrastructure and emergency response risks must be considered.

Security failures can remove significant blocks of generation at once, undermining claims that such development improves local resilience.

Disproportionate impacts on rural communities

East Durham communities are absorbing the visual, environmental, and security impacts of national energy policy, while much of the energy generated is exported beyond the area. This raises concerns under:

CDLP Policy 6 (Development on Unallocated Sites), which requires development to respect settlement character and avoid harm to residential amenity, and

Policy 29 (Sustainable Transport) where construction traffic affects rural roads and villages.

At the same time, urban rooftops, employment land, brownfield sites, and car parks—all supported in principle by the Plan—remain underutilised.

Conflict with protection of Best and Most Versatile agricultural land

Large ground-mounted solar proposals in East Durham risk the loss of productive agricultural land, contrary to CDLP Policy 19 (Best and Most Versatile Agricultural Land), which seeks to protect Grades 1, 2 and 3a unless there is an overriding need and no reasonable alternative. The Local Plan expects applicants to demonstrate that lower-quality land or previously developed land has been prioritised, which is often not evidenced in practice.

Siting driven by grid proximity rather than policy-led suitability

In East Durham, solar sites are frequently promoted primarily due to convenient grid connection, rather than alignment with landscape, soil, or settlement policies. This approach conflicts with the plan-led system underpinning the Local Plan, particularly Policy 1 (Sustainable Development), which requires development to be appropriate to its location and to avoid unacceptable harm.

Failure to assess cumulative landscape and countryside impacts

Solar applications are commonly assessed individually, despite multiple schemes being proposed or operating within the same character areas. This is inconsistent with:

CDLP Policy 10 (Green Infrastructure), and

CDLP Policy 39 (Landscape),

which require protection of landscape character and proper consideration of cumulative impacts. Incremental solar development risks eroding East Durham’s rural character in a way that is not captured by site-by-site assessment.

Absence of a clear siting hierarchy conflicts with Local Plan intent

While the County Durham Local Plan supports renewable energy in principle, it does not establish an enforceable hierarchy requiring rooftop, brownfield, and previously developed land to be prioritised over open countryside. This gap has allowed speculative greenfield solar proposals to come forward in East Durham, contrary to the spirit of Policy 1 (Sustainable Development) and Policy 6, which together expect development to be genuinely plan-led rather than opportunistic.